In her NYT bestseller Jesus and John Wayne, Kristin Kobes Du Mez (writing at

) traces militant masculinity within American Christianity, particularly through the 20th century. One key finding is how white Christian men continually looked for (and repeatedly found) a new threat to “Christian America” to confront and subdue using righteous violence.

Communism, atheism, Islam—all were external threats useful in creating a clear boundary around “us” and “them.” One of my favorite parts of Du Mez’s book, though, is when she reveals the pivot in more recent years where the new threat now begins to come from within our country. The enemy now walks among us. . .

Growing up evangelical I was drawn to the sometimes violent but always exciting Bible stories where those who are on God’s side claimed victory over their enemies. As I write about the idol of violence inherent to Christian nationalism in AMERICAN IDOLATRY,

“David picking the five smooth stones and slaying Goliath, Gideon outwitting and slaughtering the Midianites, the Red Sea crashing down on all the Egyptians, Samson exacting his revenge in the end—these were stories told and retold through felt boards, illustrated children’s books, and second-tier animation.”1

While we were taught that hurting others was usually “bad” and should be avoided, there were times where God’s people had to crack some skulls, bloody some noses, take no prisoners. We were primed to love some of the famous depictions of manly-men employing violence against their enemies—people like William Wallace and Maximus from Gladiator.

These folks were used in sermon series, and spiritualized, but the corollary was there. Christian men had to be ready to fight and defend at a moment’s notice. And just like Jesus had to braid a whip and is coming back at the End Times to shed all the blood, or David, Moses, and Gideon had to pick up the sword, I might also be asked to violently defend my own body, my family, or my country.

And while distinct ethical frameworks exist across Christianity for justifying personal or collective uses of violence, Christian nationalism blurs those lines. Again, as I write in AMERICAN IDOLATRY,

“Christian nationalism considers the use of multiple forms of violence to defend one’s body, family, community, or nation to be aligned with God’s will. The world is a dangerous place, and sometimes we need good guys with guns or the nation’s military to restore order.”2

As we look at scholarly research, we find consistent evidence that Americans who embrace Christian nationalism are more likely to agree with both individualized and collective forms of violence. Throughout our nation’s history, war was and continues to be central in refining the Christian nation narrative. Phil Gorski and Sam Perry’s book has a great chapter on this history.

Regarding collective violence, Christian nationalism is significantly and positively associated with:

Believing military actions that benefit the US are justified.3

Believing the war in Iraq was justified.4

Believing the government should expand its authority in order to “fight terrorism.”5

Regarding individualized violence, Christian nationalism is significantly and positively associated with:

Support for police when they use violence toward racial minorities.6

Support for the death penalty.7

Support for violence in order to advance political goals.8

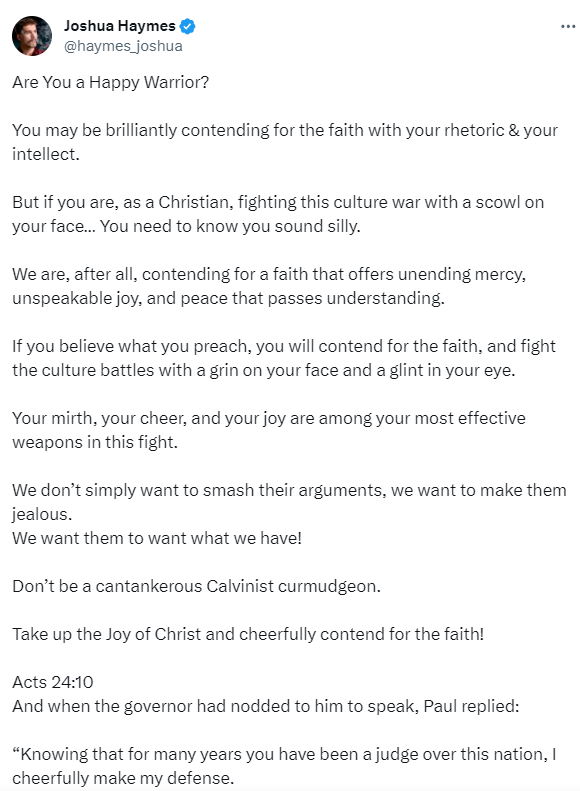

So when I see posts like this one:

That then includes the photo from above—a smiling man wearing medieval full-body armor9, carrying a sword, with a Christian cross on his chest, I see evidence of the idol of violence inherent to Christian nationalism.

While overtly spiritualized, it blurs the lines between the physical and spiritual. The Bible itself is no stranger to borrowing the language and symbolism of war (see Paul writing about the “armor of God”). But was Paul writing about putting on armor as a defense against fellow humans?

And the key for us now is that this culture war, according to Christian nationalism, is to be fought within, against fellow Americans. The enemy is no longer in the spiritual realm alone or even from the outside but among us. Fellow citizens who are not “with us.” And in order to win the culture war, we need to be ready to do whatever it takes.

Pairing this with dehumanizing language toward those who might vote differently or support alternative policies to those deemed “righteous” makes for a volatile situation.

When does the “culture war” devolve into a physical one? When does focusing on battling “political enemies” shift into physically attacking them?

“History demonstrates how violence is the result of quests for power that are based on fear, especially when power and fear revolve around hierarchical relationships predicated on ‘us’ versus ‘them.’”10

As we come up on the anniversary of January 6th, I think it is important to keep in mind how quickly violent rhetoric can turn to physical violence. How talk of overcoming “enemies” and dehumanizing “them” can legitimize taking up a sword.

Violence is a central idol of Christian nationalism and romanticizing conquering warriors is a dangerous path to encourage.

If Christians are called to reflect the example of the author and perfecter of our faith, it isn’t a sword we should be willing to take up.

Page 108 from AMERICAN IDOLATRY

Page 108 from AMERICAN IDOLATRY

See TAKING AMERICA BACK FOR GOD and Froese and Mencken (2009)

See Armaly et al. (2022) and PRRI’s 2023 Survey

Hmmm. . . what sorts of religiously legitimated violence took place during the medieval period?

Page 17 from AMERICAN IDOLATRY