Christian nationalism should guide the nation. Just don't call us Christian nationalists. (Or: "Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!")

Ongoing attempts to redefine Christian nationalism underscore why it is important to keep the empirically-supported definition front and center.

In the six years that my work on Christian nationalism has garnered more and more public interest, one thing has become clear:

Clearly communicating the empirically-supported definition of Christian nationalism is the most important aspect of my role as an academic engaged in public translation of my own and others’ research in this area.

With so much new data and analysis appearing every few weeks, it’s easy to want to jump from one interesting finding to another to share with various audiences.

But as public awareness of the term “Christian nationalism” grows alongside well-executed social science research, the mobilization of those who feel threatened by such attention results in one of two responses:

“Christian nationalism doesn’t exist and is just a made up term from those who want to keep religious Americans from bringing their faith into the public sphere”,

“Christian nationalism exists, I’m a Christian nationalist, but all Christian nationalism means is I want to bring my faith into the public sphere”

Doug Mastriano, former candidate for Pennsylvania governor, is a good example of the first response. While explicitly arguing for the close fusion of a particular expression of Christianity with social and political life in the United States (almost a literal definition of Christian nationalism), he denied doing so meant he embraced Christian nationalism.

Marjorie Taylor Green, Republican from Georgia, is one example (among many) of the second response. This group tries to change the terms of the discussion, redefining Christian nationalism (absent any empirical support) as merely a publicly-engaged Christianity to serve their own purposes.

Both responses are attempts to minimize, deflect, muddy the waters, and ultimately keep what was unseen as unseen. Each response recognizes the threat inherent to naming and clearly identifying Christian nationalism.

All this leads to why I was excited to see some insightful new data and analysis pertaining to my ongoing experience.

New research and analysis from Paul Djupe1 provides some much-needed perspective on how Americans respond to the term “Christian nationalism,” what Christian nationalism is, and the role it plays in the nation’s future.

I’d like to lead with his conclusion, as it powerfully sums up what he found:

It seems clear that many Christian nationalists do not like being labeled as such even as they see Christian nationalism as a substantive idea that they agree with for restoring Christians to societal dominance. The elite ploy, of course, has been to try and delegitimize opponents who are accurately labeling them. And they use accusations that opponents are trying to take away their rights by calling them Christian nationalists to feed the Christian persecution complex that has been so successful at mobilizing supporters. The fact that those feigning outrage are actually supporters is unlikely to stop them.

Using a national sample of American adults collected earlier this year, Paul and colleagues asked respondents if Christian nationalism was a “term invented by the left to smear conservative Christians.” Just over 40% agreed or strongly agreed.

They also asked for respondents’ level of agreement with another really important and revealing statement, however: “Christian nationalism is the only idea that will save this fallen nation.”

Of those who agreed Christian nationalism was just a made-up smear—68% agreed or strongly agreed that Christian nationalism is the only way to save our nation.

At this point, I strongly urge you to go check out the first visual Paul created—I won’t reproduce it here as his blog deserves the clicks. It demonstrates how the majority of those who say Christian nationalism is just a smear on Christians likewise believe Christian nationalism will save the nation.

But wait—could it be that these folks just define Christian nationalism as “Christians just bringing their faith into the public sphere” and not something akin to a “close fusion of a particular expression of Christianity with social and political life in the United States”?

Paul covers that:

The savior statement could still be seen as anodyne support for democracy, except that agreement with Christian nationalism as both smear and savior is also strongly associated with support for the statement that “God wants Christians to stand atop the ‘7 Mountains of Society’ (government, education, business, etc.)” (see the figure below). Moreover, all three of these statements are strongly correlated (r~.5) with our attempt to measure the content of Christian nationalism with six standard items used across political science and sociology, including “The federal government should advocate Christian values for the benefit of Christians.” It is clear that smear/savior Christians are Christian Nationalists who believe in the divine mandate to exercise dominion over the US.

That’s right—these respondents believe 1) Christian nationalism is just a made-up smear, 2) Christians should take dominion over society, and 3) Christian nationalism is the only way to save our nation.

This analysis is so revealing, and important, in that it underscores how ongoing attempts to redefine Christian nationalism or deflect during conversations about its implications for civil society in the United States are really about maintaining a level of ignorance and nurturing “the Christian persecution complex that has been so successful at mobilizing supporters.”

Only by encouraging confusion about what Christian nationalism is can folks who embrace it ignore the growing body of evidence showing how it really does undermine the values inherent to a pluralistic, democratic society.

In other words, it’s a version of “pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.”

This subset of Americans wants their particular expression of Christianity to have power, they believe this is the only way to save the nation, but they do not want this pointed out to them or others.

And so I really must include a review of the empirically-supported definition of Christian nationalism backed by dozens of peer-reviewed studies and books (you’ll find this definition near the end of my last post):

Christian nationalism is a cultural framework—a collection of myths, traditions, symbols, narratives, and value systems—that idealizes and advocates a fusion of a particular expression of Christianity with American civic life.

It holds that this version of Christianity should be the principal and undisputed cultural framework in the United States and that the government should vigorously preserve that cultural framework.

While the particular expression of Christianity referenced in Christian nationalism does refer to theological or orthodox beliefs, it includes four elements that underscore the threat it poses to a pluralistic, democratic society.

A desire for a society organized according to traditionalist social arrangements. The ideal society is one where men lead and women support, marriage is ideally heterosexual, and families with a mom and dad are committed to procreation. American citizens and families that represent these ideals will have the easiest access to civil rights and liberties. Those who do not embrace these ideals will consequently be denied easy access.

A comfort with authoritarian social control. The world is a viewed as a chaotic place and we need strong leaders who through the threat of violence, or actual violence, defend the preferred social arrangements and hierarchies.

A desire for strong ethno-racial boundaries around national identity, civic participation, and social belonging. The ideal American is generally understood to be a natural-born Anglo Protestant. It is this group who created the United States, and it is this group who should remain central to its cultural identity and political leadership.

A populist impulse that creates space for Americans to embrace feelings of victimization—that certain “elites” are trying to persecute them—which lends itself to adopting more conspiratorial thinking. One example of this is thinking Christians in America are being silenced or persecuted.

So when folks want to know what Christian nationalism is—the above is the empirically supported definition.

We need to continue to state the definition clearly so folks know Christian nationalism isn’t just about bringing your faith into the public square. It’s about seeking privileged political and cultural power for one particular expression of the Christian faith at the exclusion of everyone else.

Additional news

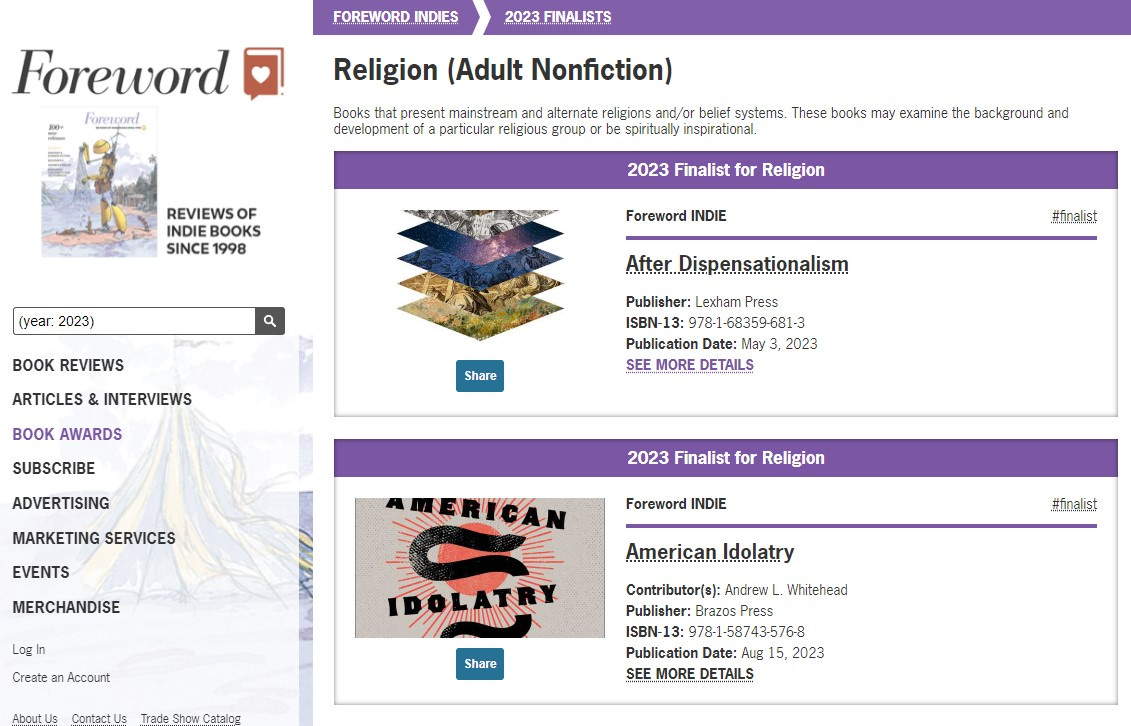

AMERICAN IDOLATRY was chosen as a 2023 finalist for FOREWARD Indies Reviews for the non-fiction Religion category! This was super encouraging. If you have read the book, consider leaving a review at one of the online marketplaces. It really does help.

Once a month I’m joining The New Evangelicals to recap recent Christian nationalism research, CN in the news, and then share resources for those interested in finding a new way forward. Follow along on The New Evangelicals’s various social accounts like YouTube, podcasts, etc.

Finally, I'm excited to share two upcoming events centered around my research on Christian nationalism in the United States. I hope to see some of my Texas connections at one or both!

First is an invited talk at my graduate school alma mater, Baylor University, on March 26th in the afternoon. I'm forever grateful for my time at Baylor and this invitation means the world to me. I can't wait!

Second is a conference I'll be participating in focused on Christian nationalism and sponsored by the Religion and Public Policy program at the Baker Institute and the Boniuk Institute for the Study and Advancement of Religious Tolerance, both at Rice University.

It's an all-day affair with 5 different panels featuring some outstanding folks: Sam Perry, Tim Alberta, Angela Denker, Willie Jennings, Jonathan Tran, Glenn Bracey, Jerry Park, Rachel Schneider, Kevin Dougherty, Eric McDaniel, David Leebron, Ruth Braunstein, David Brockman, and Paul Miller. Find out more here.

Texas continues to be an epicenter of Christian nationalism in the US. Please spread the word about these two opportunities to participate in the ongoing conversation.

Follow Paul’s work at the Religion in Public blog which is a veritable fount of accessible columns highlighting a range of interesting social scientific findings regarding religion, politics, and culture.

How do you respond to the idea that CN should be called some variant of Christian Fascism instead of Christian Nationalism? It seems to me it would be more of an attention-grabber but could also be unhelpful since there are some people on the fence about CN who could be persuaded that it's harmful, but they may not be willing to listen after being labeled fascists.

It’s what cults do when they try to hide what they really are. There’s a need for a Confessing Church right about now, because this is some apostasy.